Americans are getting heavier and more sedentary, with an ever increasing prevalance of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, with subsequent development of vascular and kidney disease.

A June, 2014 update from the CDC says:

9.3% (~1 in 11) of Americans have diabetes, and 1 in 3 Americans have prediabetes

Total annual cost of diabetes = $245 billion

Losses from disability, work loss and premature death = $69 billion

Medical costs = $176 billion (adjusted for age and sex)

Medical costs that average 2.3 times more than for people who don’t have diabetes.

They don’t itemize it, but those increased costs are for all the blindness, thrice-weekly dialysis treatments for kidney failure, heart attacks, strokes and amputations.

Even though type 2 diabetes is a non-communicable disease (meaning it’s not an infection), it is becoming an epidemic. Looking at the percentage of American who have diabetes:

In 1994: 4.4%

In 2004: 6.9%

In 2014: 9.3%

In 2024: 12.8% ?

How much can a country spend on medical care before there is not enough to spend on living well - safety, a warm home, nourishment, education, a good job and reliable transportation?

Nobody knows, but many fear that we’re on a path to find out.

More important, why is this happening?

We think that one key reason it’s happening is that our society over-invests time, money and energy in treating the problem - disease care - without investing much in the underlying causes.

85% of health outcomes are caused by social / behavioral factors in a person’s life; but only

15% of health outcomes are caused by medical care and patient adherence to medical advice.

Our health care system is really a disease care system that focuses on the 15% of causes:

Does the patient take his or her cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar and blood thinning medications;

Do patients get adequately screened for vision, kidney failure and circulation problems;

Do doctors follow all the guidelines;

Does a care manager follow-up to avert missed appointments and gaps-in-care;

Is the health network accountable for these operational performance parameters?

Meanwhile, we don’t cut off the fuel supply, so the fire of chronic diseases blazes away, unabated.

Hey gang, really now, this approach of surgery and magic pills on the 15% ain’t gonna work.

We’ve got to start working in earnest on the 85%, too.

If we don’t make a change, what is it going to look like? Well,…

Employers

Will have to drop health insurance benefits for employees;

Physicians

Will be overwhelmed, with almost half the population on chronic medication:

(Really, do ½ of all Americans need to be on a medication?)

Hospitals and Health Networks

Being held accountabile but with limited influence over 85% of the causes….expect disappointing results;

Dieticians and Exercise Physiologists

Are anxiously standing idly-by, desperately wanting to be put in the game;

Parks and Recreation Managers

Also under-funded and greatly under-appreciated for contribution to health and vitality;

Patients

Can expect a morass of medical appointments, having to go on disability and feeling trapped in the waiting rooms of health professionals.

Our health care system unintentionally pushes people towards chronic disease, disability and frailty, rather than towards prolonging their vitality and well-being.

Repeat: our system fosters chronic disease, disability and frailty.

Nobody wants that, but it’s what we get from investing so heavily in medical procedures and pharmaceutical solutions (the 15% side), and so minimally in health ecology causes (the 85% side).

The components of a person’s ecological network, what we at Sustainable Health call health ecology, are:

Individuals - you, for example;

Vested stakeholders - employers/insurers, physicians, hospitals and health care networks;

Non-vested stakeholders - dieticians, exercise professionals, social workers, psychologists, nurses, nursing aides, health educators; and

Common-pool resources - parks and trails managers, local agricultural producers and vendors, grocers, transportation services, financial services, etc.

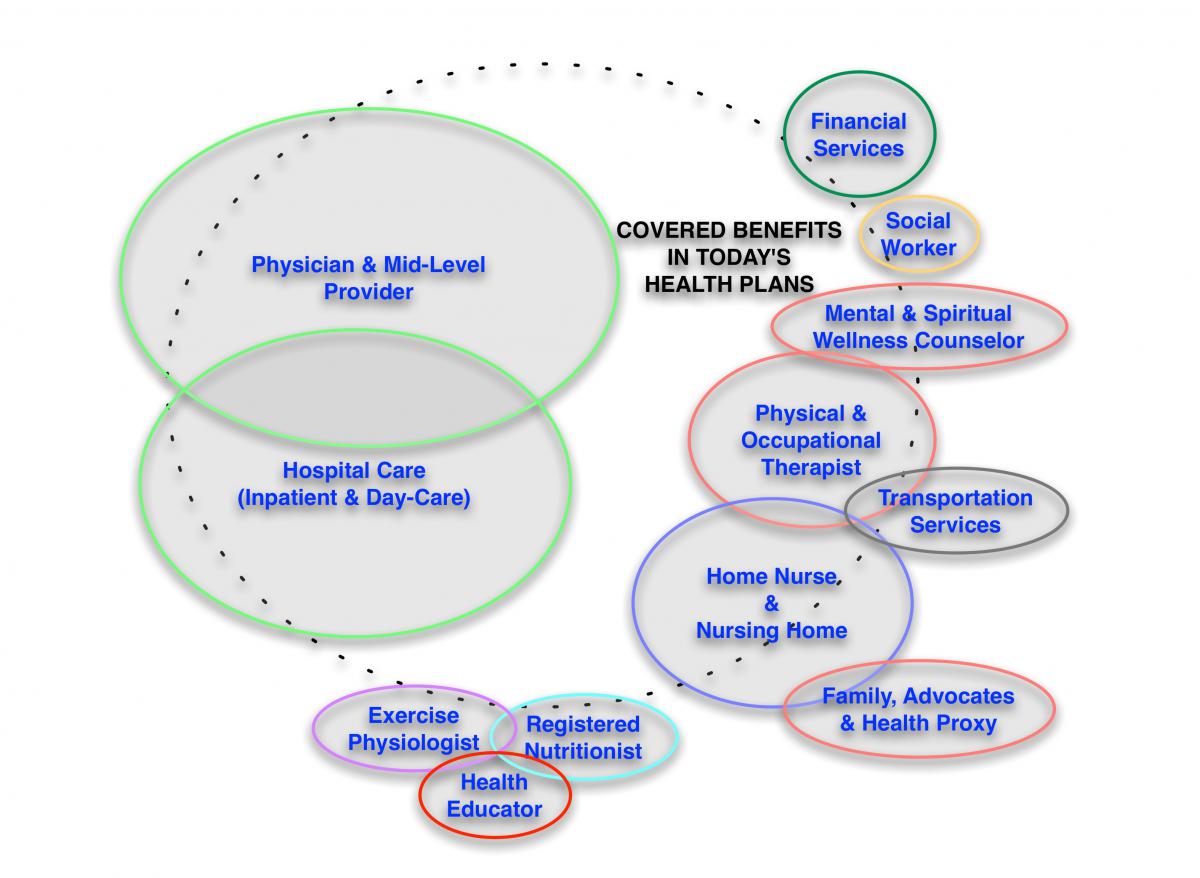

Contrast a Venn diagram (Figure 1)

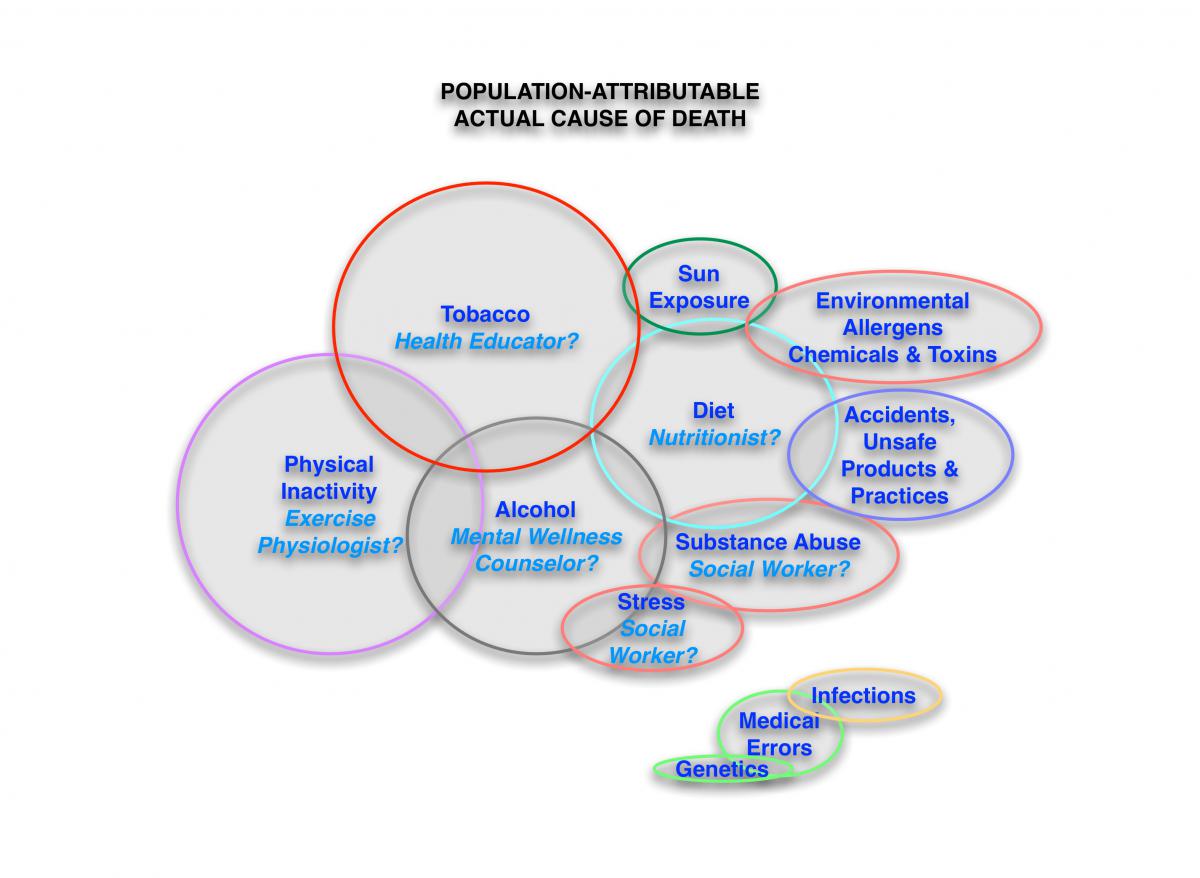

that examines covered services of typical a health care plan, with a Venn diagram (Figure 2)

that examines covered services of typical a health care plan, with a Venn diagram (Figure 2)

representing the population-attributable actual causes of death (and morbidity / chronic disease). The health profession services in alignment with the actual causes (i.e., nutritionists, exercise physiologists, social workers, psychologists, transportation workers, etc.) are minimally covered in today’s health plans.

These non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources are partially subsidized through state public health programs, grants, charity and through cost-shifing (often in discounted dollars that come from the vested stakeholders). Relying on public funding, non-governmental not-for-profit organizations and goodwill creates a patchwork of services from these professions and is not going to work well. That public health model is W E A K because is doesn't link the patient's main health mentor (his or her primary care physician) with resources to address the 85%. It just perpetuates the silos for the vested stakeholders.

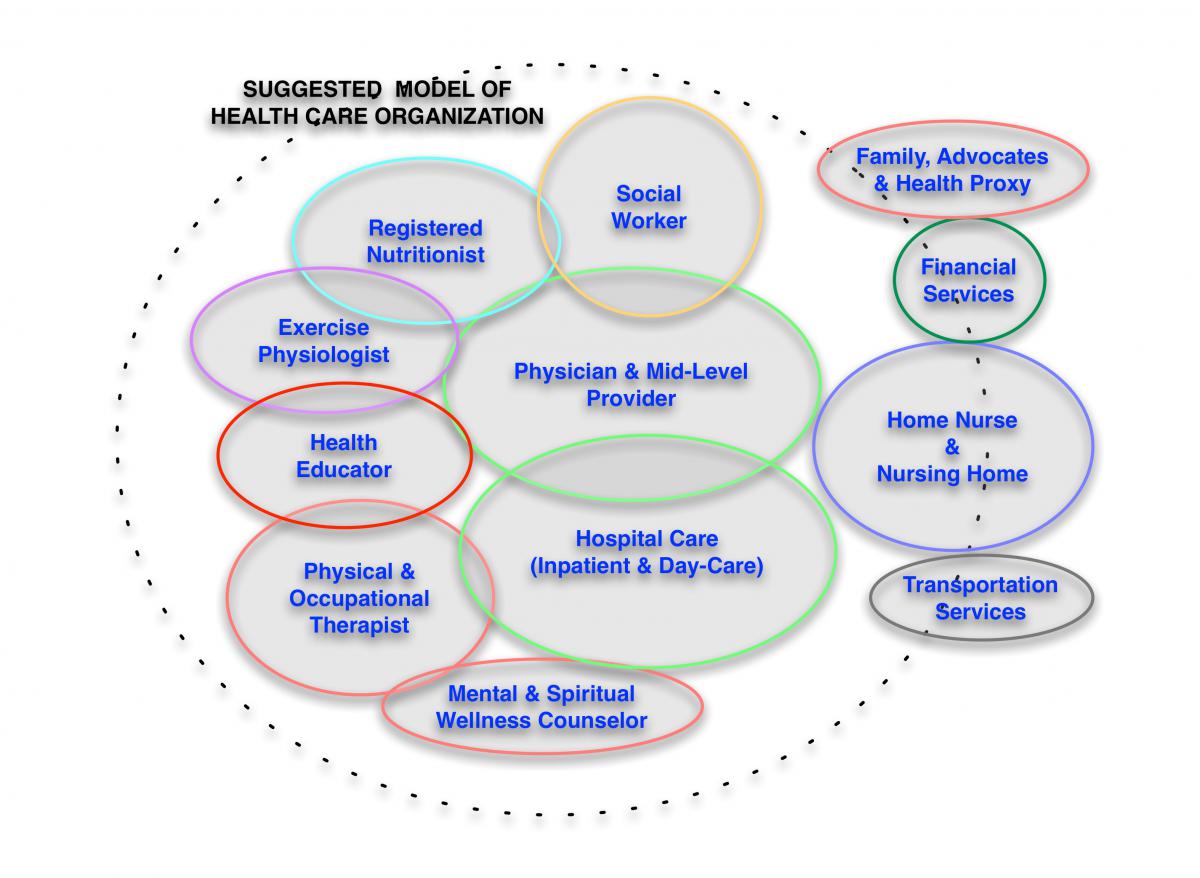

We think an important step (Figure 3)

is to bring the non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources into the system, recognizing their roles and providing them a sustainable business model.

is to bring the non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources into the system, recognizing their roles and providing them a sustainable business model.

Compared to what we’re spending on informatics, very little is being invested in:

• Bringing the non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources into the system,

• Providing a social networking solution to help patients engage with the non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources, and

• Creating a market mechanism that properly values the non-vested stakeholders and common-pool resources for their potential contributions.

So what is this rush on health informatics supporting? The needs of patients, or of computer technology companies?

Health care leadership needs to enable these potential stakeholders who are currently being left out of the system, raise everyone’s awareness of their potential roles and then convene everyone to discover collaborative solutions.

If world history provides any insight, it is that denial by the vested stakeholders will take us to the brink of economic catastrophe before they examine their own beliefs and begin to call for change. Is anybody out there who can learn from the mistakes of our forefathers, or are we really going to do this?

Geoffrey E. Moore, MD FACSM

Peter G. Sepsis, MS MPH

- GE Moore MD's blog

- Log in to post comments

- Follow our Blog