A recent headline in the Times of London (England) stated, “One in Three Now at Risk as Diabetes Levels Soar”. One public health official quoted in the article said "If a doctor sits you down and says 'If you carry on they way you are going, I believe within two years you will have diabetes, or heart disease, or cancer,' you will get people to sit up and take notice”. Take notice? Maybe.

Perhaps patients would pay closer attention to, and have a greater likelihood of modifying, health behaviors if physicians gave appropriate motivational impetus and had the requisite tools to provide support. Research shows that patients have a greater tendency to exercise and quit smoking if they have been advised to do so by their physician. With the alarming increase in prevalence of lifestyle-associated chronic conditions, physicians need to do a better job of addressing modifiable risk behaviors such as exercise, diet and tobacco use.

The challenge is in creating a systemic approach that captures the moral imperative that can be provided by physicians, but uses community-based allied health care providers to provide the interventions.

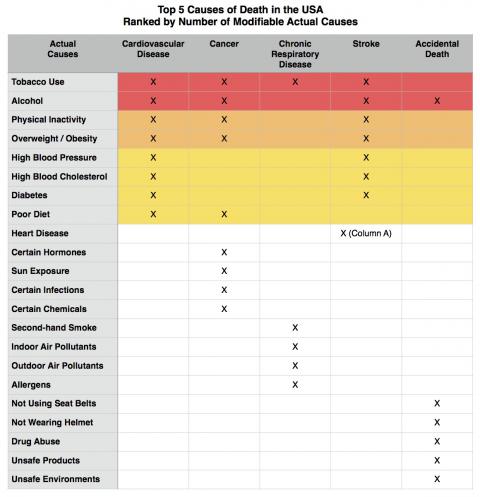

In the USA, medical services determine only 5-15% of health outcomes. The overwhelming majority of both mortality and - more important - the burden of chronic disease are determined by:

1) Personal behaviors,

2) Environmental and social factors, and

3) Family history and genetics.

Thus, as health care in the USA increasingly moves to an accountable care model, physicians and hospitals may soon be financially punished for health outcomes that are, to an enormous degree, not their fault. Is that really a good idea?

Instead of punishing physicians and hospitals for problems that are not their doing, health care networks should start to address the 85-95% of the determinants of chronic disease and mortality. Unfortunately, almost all the transformational efforts are being directed at the the part of the health care system affecting only 5-15% of outcomes. It’s not hard to predict that the current reform efforts are likely have a small overall effect!

To create a big effect, health care systems need to address personal behaviors, environmental and social factors. Doing so will require health care teams to adopt tools from epidemiology and behavioral medicine, in order to systematically address 2 key issues:

1) Assess health ecology (i.e., measure the patient’s relative contributions of the personal behavior, environment and social factors), and

2) Guide those patients who have significant barriers to health improvement to appropriate local resources in their community.

The logical integrative step is to tie these functions together by enabling physicians to coordinate these efforts at improving health ecology. Since people do pay heed to what their physician advises them, we agree with the Times of London article and think it makes sense to empower physicians – especially primary care physicians – with this role.

The Affordable Care Act provides primary care physicians with the perfect opportunity to do so in the Annual Wellness Visit. For so-called “apparently healthy” individuals (a phrase that implies lurking conditions), the Annual Wellness Visit is an opportunity to systematically capture the ecological risk factors that determine poor health outcomes. If the patient and physician discuss and agree to address the modifiable risks, they can work towards improving his or her health ecology.

For individuals who already have a chronic condition (which usually have underlying ecological factors), the Annual Wellness Visit is an opportunity to focus on personal behaviors and barriers to improving health. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was terminated early because it was deemed unethical to withhold the lifestyle intervention from the cohorts that were assigned metformin or placebo. Like the DPP, it makes no sense for someone who has a chronic condition to just use medical care, but not address health ecology and passively let patients continue adding fuel to the fire.

So, if physicians do this, will they, as the UK health official said, "get people to sit up and take notice"?

Maybe a better question is that with physicians, hospitals and health care networks financially on the line for health outcomes, can they afford to take the risk of not addressing those 85-95% of determinants?

Peter G. Sepsis, MS MPH

Geoffrey E. Moore, MD FACSM

REFERENCES

Russell MAH, Wilson C, Taylor C, Baker CD. Effect of general practitioners' advice against smoking. Br Med J. Jul 28, 1979; 2(6184): 231–235. PMCID: PMC1595592

Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, Sloan ML, Lullo C, Visser SN, Fox MH, Armour BS, Campbell VA, Brown DR, Dorn JM. Vital Signs: Disability and Physical Activity — United States, 2009–2012. MMWR 63(18); 407-413.

McGinnis J, Foege WH. Actual Causes of Death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207-2212. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03510180077038.

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004; 291(10):1238-1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238

McGinnis J, Foege WH. The Immediate vs the Important. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1263-1264. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1263.

Yoon PW, Bastian B, Anderson RN, Collins JL, Jaffe HW. Potentially Preventable Deaths from the Five Leading Causes of Death — United States, 2008–2010. MMWR 63(17); 369-374.

US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of US Health, 1990-2010: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-606. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.13805.

The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

- GE Moore MD's blog

- Log in to post comments

- Follow our Blog